|

I nearly didn’t go this year – work was busy, and 2020 had already induced massive Zoom fatigue. But I was intrigued by the promise of the conference, so I registered, tested the new platform, and dipped in, and the 2021 Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference was not just a silver lining of the pandemic for me – it turned out to be a platinum lining.

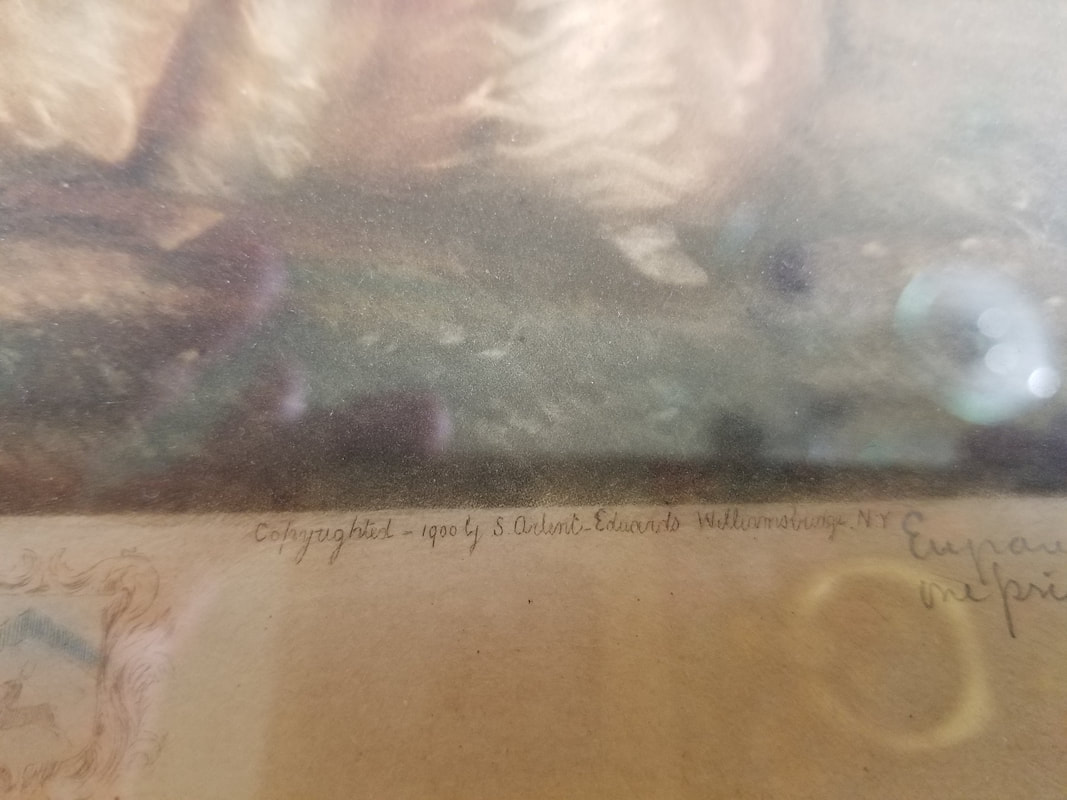

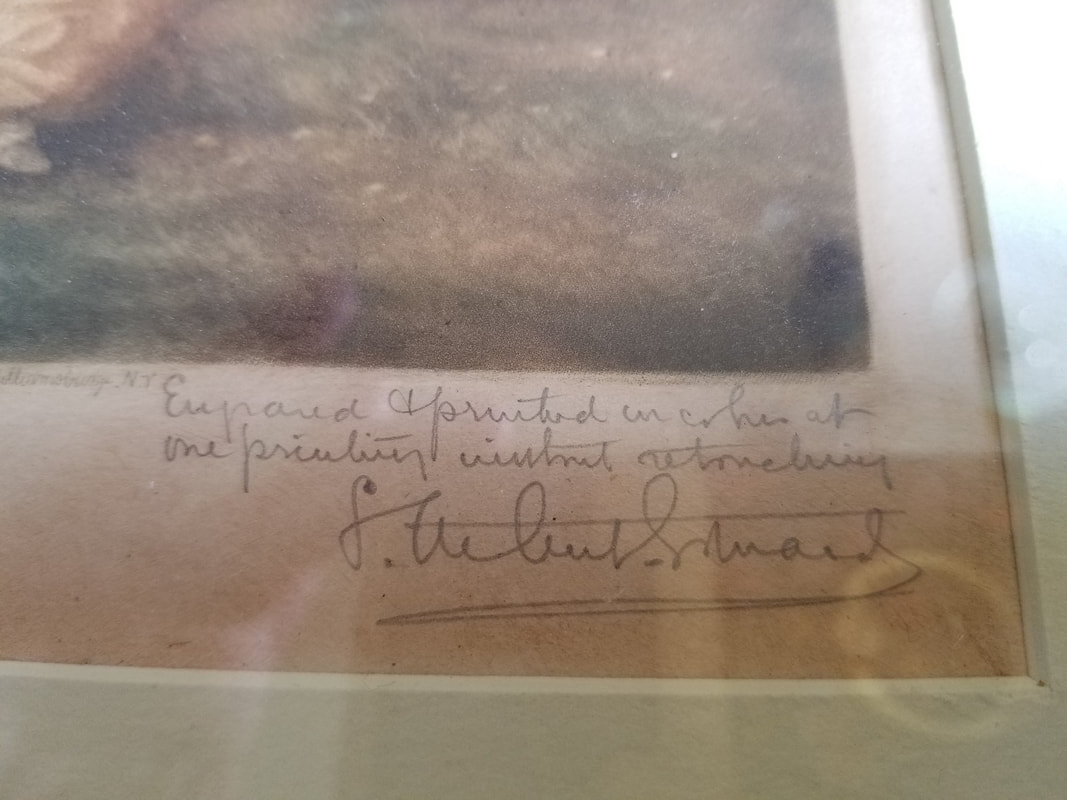

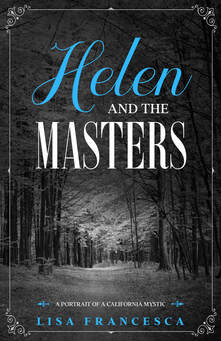

Let’s take a step back. I’ve been to two other AWP conferences. Seattle (2014) was my first, I was alone, and my adrenalin rushed the entire time. Navigating three hotels and downtown Seattle, I made it to two or three panels and a keynote, and spent two full, full days at the book fair (imagine: a football field full of tiny tables of books. And tchotchkes). At the end, I left my clothes at the hotel and packed books and magazines in my suitcase instead, tossing it into the plane’s overhead compartment and developing frozen shoulder that required months of physical therapy. Talk about memorable. I brought home better souvenirs, though. That sweet, crazy sensation of being surrounded by more than 14,000 people who loved writing. Two publishers who said they’d like to see my work. I heard Gary Snyder read. And I began to work seriously on a biography that would take seven years to complete. Then there was Tampa (2018), an excuse to visit Florida in early spring. I talked my husband into coming with me and we explored the river city at night, hearing readings in galleries and cafes. I think I saw four panels that time. We listened to George Saunders, enchanted. I had a mission to pitch my biography, but never found traction. The crowds were overwhelming and not quite as charming as the first time. Still, this time I brought home subscriptions to beautiful literary magazines, along with pins (Read Local! Today I Shall Create!) and pens and a book about how to manage the business of writing. This year, the organizers pre-recorded the sessions and those panels remained accessible for three weeks. This one move elegantly removed my greatest AWP frustration – wanting to attend simultaneous panels. Like the other years, I selected about 25 events without hope of attending them all. I was wrong. The conference lasted five days, but the recordings are still up as I write this post. I have listened to 24 panels in 12 days, most of them all the way through, and found ten more to attend next week. It’s been like an MFA on steroids. There’s an art to managing the online panels. I like to examine the chat history first, because both panelists and attendees often list interesting links and tools. I download the files that the panelists provide, sometimes pages of tips or booklists. Then, as I listen, I check out the panelist biographies and what reviewers have said about their books-- unless I’m taking notes on what they are saying. Or I stretch and do pushups while listening. I’ve thanked panelists and they’ve written back! I’ve completely filled a new notebook, and certain things I’ve learned have informed how I’m going to write this new book that has me firmly in its jaws. And because there were no plane or hotel fees, I allowed myself to buy books – like, thirty of them (something I’ve never done before): poetry, essays, craft books, novels, biographies. Books that AWP panelists and attendees collectively raved about – from independent presses when I could, and from Amazon, because budget. I also listened to conversations about helpful ways to publicize one's small or self-published book, and ways to make money in the meantime, and how to teach different groups to write. I heard from writers over fifty, and Appalachian writers, and Muslim poets, and poets who write nonfiction, nature writers, and screenwriters. . . . And I got to watch national Poet Laureate Joy Harjo’s magical jazz poetry session three times, and she’s that great, that amazing. Now books are arriving on my porch a handful at a time, a couple of new subscriptions will kick in, and I’m feeling fortified with Vitamin AWP for another few years. I didn't stay up late once, or have to find a seat in a smoky bar. When I go again in person, it will be fun, and new in a hundred different ways. But I doubt that it will top this intensive, private education -- one panel at a time, in my sweatpants, eating my own sandwiches. This was a colossal gift.  I’ve been writing one book in particular since about 2014. First, it served as my MFA Nonfiction thesis. When it was accepted by the committee, I chose to embargo its academic publication. I wanted to give this little book a chance to be published before it became fodder for future academics and scholars. But the question of who would publish it grew tough. Who would read a story about a woman in the early twentieth century who becomes a medium for interesting voices, through automatic writing? A woman who, unlike Sarah Winchester, did not become famous. And unlike Jane Roberts or Sylvia Browne, did not publish her writings for a commercial audience. My book seemed to be too much of a family story to be literature, but too lyrical to be a straight-up biography. While I hunted for publishers and agents, the entire book had to be overhauled anyway – the academic tones rinsed out, and new transitions inserted. Pieces I loved all the way to the last draft had to be ruthlessly axed, while other items from an early draft marched back in. From 2017 through early 2020, I alternately cast it down and took it back up. I hated myself when I wasn’t writing, a common writer trait. I began to bargain with my Higher Power. ‘Show me what to do,” I demanded. “Make it really obvious!” The first break in the mist was an email from my uncle, saying he’d help me publish the book for the family. I began to realize that this was an offer of real freedom – I would not have to change the book to fit the agenda or category for an agent or a publisher. Then the pandemic arrived, changing my daily routines -- no more commute, no movies, no restaurants, no gatherings. Many people talk about how they are cleaning their closets and gardening during this COVID era. I don’t have a garden and in 2020, most of my worldly goods were in storage. So I came back to the book. I kept coming back until one day, it felt done. Then a good friend decided to self-publish using an online behemoth you all know – and she told me how easy and straightforward the process was. She was right! Within two weeks I had a cover design, a formatted interior and an ISBN number. Thanks to my uncle, I was able to order about 50 copies of that little book and gift them to family members. Sending all these good people a book that I wrote about channeling spirits through automatic writing was a bit like going to a big reunion and taking my clothes off. I wanted to go into hiding for a few months until I felt safe again. But I finished the book, and I made it the very best I could. The response has been warm and positive. Writing the book grew me as a writer and as a historian, and as a member of my communities. And I am pleased to realize that, whatever good readers can find in it, by bringing their own spacious minds to interact with the page, that is a little bit of good that would not otherwise have existed in the world. That scrap of good is my legacy. Helen and the Masters: A Portrait of a California Mystic is available as a paperback on Amazon. My mother was packing in preparation for a move. "Would you like to take this home with you?" she asked. "I'm not sure but it may have belonged to my mother." I liked the image, and took it home. Two years later, I was packing in preparation for a move. This print of the lady had been on my wall but frankly, it had not added a lot to my decor. It's a very quiet image, and the colors are a little muted, though warm. I called Mom and asked about it, but she couldn't remember any other details. Without a compelling family story, I wasn't sure this print would make the cut. But like anyone who's read Marie Kondo's The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up, I sat down one more time to really look at the image, and perhaps thank it before releasing it. That's when I saw this: Who was S. Arlent Edwards, where was Williamsbridge,New York, and why had he handwritten the copyright, I wondered. Then I saw this rather extraordinary statement, which, it turns out, accompanied much of his work: "Engraved and printed in color at one printing without retouching"! Turning aside from all the office work that I should have been doing, I began my research.

The plate was likely destroyed very soon after this print of the lady in the pink dress was made. Online I saw plenty of prints by Edwards, but nothing that looked like this one, so it could be rare. It appears to be a copy of "Lady Sheffield" by Gainsborough, but whereas the original is in blues, Edwards warmed up the image considerably by giving her a pink dress and bow in her hat, with a black brim as an accent. I began to like S. Arlent Edwards very much. He copied classics, which is a noble venture in itself, but then he made them his own. I learned that he was a one-man shop. Here is a wonderful description of Edwards and his mezzotint process. It's from an exhibit in the Georgetown University Library, and there are also mezzotints by Edwards in the Smithsonian. According to the curator of his exhibit, "Edwards himself inked and printed each plate for every copy, and therefore no two prints were exactly alike. He made only a limited number of copies of each work, insisting that each be sold framed, and then he destroyed each plate." "The process is unforgiving of error or impatience, but allows unsurpassed delicacy of line, color shading, and texture. It was perfectly suited to Edwards' interest in such fine aspects of old masters' work, and his attention to the details of their paintings resulted in creative reinterpretations that are far more than mere reproductions. Not only are they acts of homage, they are also original works of art in their own right." I wrote to my mother, telling her all this, in case she wanted to keep it. But now I felt affection for this print, affection for the printer, and curiosity about Lady Sheffield. What was her story? Would it be something I could research and write about? And which of our relatives chose her from a New York gallery and framing shop around the year 1900? And why did they choose this one instead of Edwards' more popular "George Washingtons" and Bellini copies? Could they have also been intrigued by the substitution of the pink dress? Mom replied, "this is great research - more power to you! (About the family members) Frankly, I don't remember - somehow I think Amistad [her father's parents' home], but it may have been Grammy, too [her mother's mother] - it doesn't much matter at this point. I just like to think of her being well cared for. . . " And maybe after all, the family story that was once attached doesn't much matter at this point. I appear to have formed my own, and the print will stay with me and my family. With some of the research in an envelope, taped to the back. Right around Thanksgiving, people start looking for wedding coordinators, wedding books, and wedding officiants. In the flurry, I'm reminded of the months I worked with my Dad, learning how he officiated at weddings.

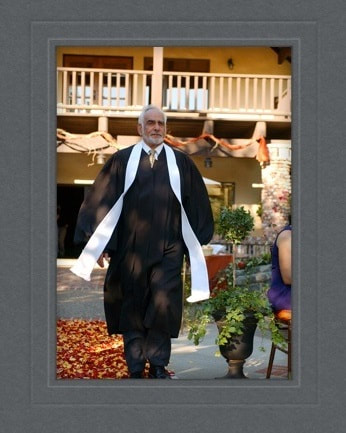

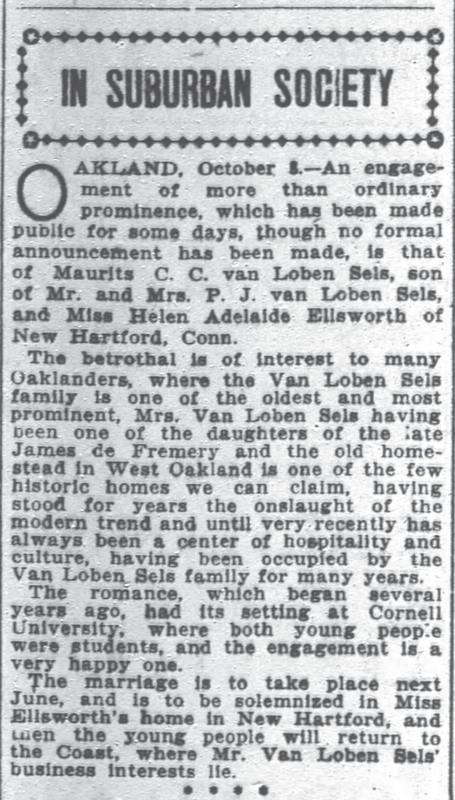

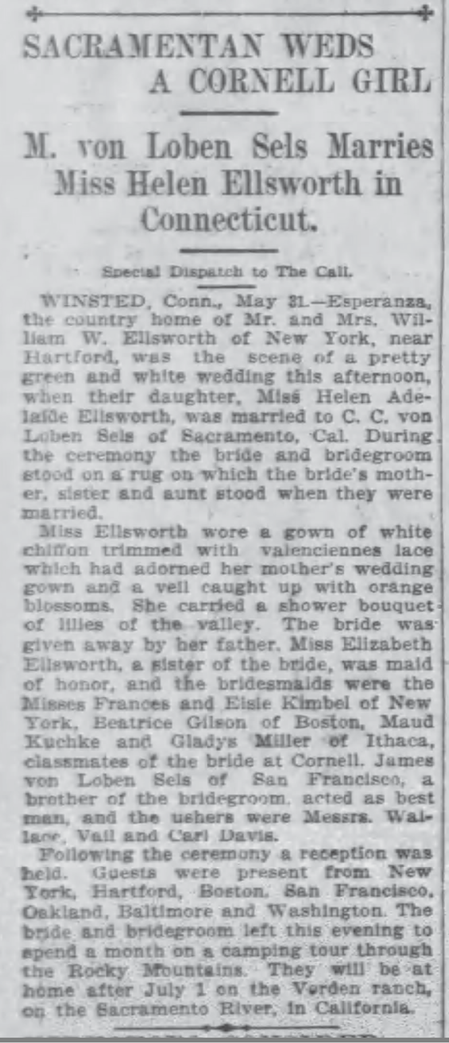

Dad had an insatiable interest in human beings, great curiosity about what made them tick. He coupled this with a sense of calm authority and warm humor, and his wedding clients found this combination irresistible. They trusted him right away, and formed longstanding relationships. A few sent him cards years later, and came to his memorial service. Dad loved the theater of a wedding. "It has everything," he explained to me. "lights, costumes, music, scripts." He loved orchestrating, and he also enjoyed sitting back and watching the other professionals, the wedding coordinator, the florist, the photographer, the DJ, do their work. Dad taught me to bring a sense of calm to the wedding. He taught me that you never know what will go awry at a wedding, but you can count on something, given that weddings are large groups of diverse people, with agendas, agreeing to show up at one place and one time. And that as long as the couple are married, everything else is really small potatoes. He maintained that calm when a groom swallowed his own wedding ring during a drunken rehearsal (it did show up, cleaned, at the wedding). He even held his equilibrium during a hot air balloon wedding. Finally, Dad taught me how to keep on being surprised by the ceremony, even as he performed more than a thousand weddings. It's easier to do this when you tailor the script to your couple, but still! "You've read your words lots of times," he would say, "but for everyone in front of you, it's the first time they really hear it. So don't rehearse it too much, and enjoy it." And I did. I've been writing my Masters' thesis, a slim biography about my maternal great-grandmother, for three years. At first the book was mostly in my head as I struggled with structure and voice. Finally, scenes began to find their way onto paper. During year two, I constructed a long, awkward 'spine' of a book with clunky pieces. I was still in the gathering and placing phase, and many of the pieces went off in all directions. It was such a mess! I shared it with friends who gently reflected back that yes, it was such a mess. Still, the book had come alive now, and we were in a rather obsessive relationship. This summer, in shifts of between one and four hours of work on it every day (and dreaming about it all the time), I managed to cut and sand away the rough edges, find an internal logic, and let the story begin to shine by itself. I didn't answer all the questions I had about her, but now I could see parts of her life more clearly. I'm a month away from submitting it to the first committee for their round of edits, and I have not performed a wedding for a year. And yet. Weddings are around me, I remember them, I think about them. Here is a clipping about my great-grandmother's engagement to my great-grandfather. . . And here is what the wedding was like: Somewhere I have a blurry grey and white photo of the couple, but I actually think the reporter's breathless words do them better justice. A gown trimmed with Valenciennes lace! Orange blossoms on her veil! My family remembers that the wedding took place in the 'keeping room' because it was a little too chilly to hold outside. The keeping room is where dairy products were kept at a steady temperature. My guess is that the milk and butter were removed, and the room was filled with flowers.

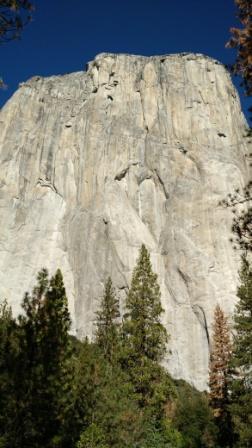

Thank you for reading, and wish me luck on this thesis.  I was staring at my tiny phone screen too long and too often. It was time to drive East four hours from the San Francisco Bay and look at something completely spectacular. Around Manteca the geological and arboreal strata began to shift. Nut trees and vineyards were gradually replaced by rolling, golden hills, which turned into to steeper, black oak-covered hills with ancient outcroppings of basalt boulders, lava remains. The dirt turned red approaching Copperopolis. A climb of the Old Priest’s trail put us in the land of sugar pines, sinuous manzanita, and tall incense cedar. We kept climbing. No matter how many times I’ve made this trip, nothing all the way past Groveland prepares me for the shocking beauty of the descent into Yosemite Valley. Mark, and I spent a long time staring at El Capitan last weekend. We stood on the valley floor and gazed up 3,000 feet to the top, maybe from the same spot where Chiura Obata painted in the early 1930s! The deep blue November sky made the whites almost painfully bright. Formed from a single chunk of granite, El Capitan is considered the largest granite monolith in the world. Millions of years ago, these mountains lay buried beneath five miles of solid rock. After meandering rivers and streams slowly wore away the rock to reveal the granites, more rapid rivers carved steep slopes and canyons. Then a glacier took eons of slow weight and power to sculpt and polish the face of El Capitan. It’s easy to get impatient when a video doesn’t load immediately, or when an e-mail goes unanswered for a few days. Look to something massive. Think about something slow. It’s good for my fevered brain. At the end of summer I signed up for a semester of Yoga and Ayurveda studies in San Jose’s brand new Meru Institute. It’s been rewarding to meditate and learn about ancient Yoga philosophies and the history of Yoga in America. I’ve enjoyed lectures on the basics of Ayurveda and Sanskrit. But last night I got homework that made me turn right back into a teen rebel.

The homework is simple enough. Eat very simply for three to five days. The menu is basic and wholesome: Fruit (in abundance) for breakfast; salad or steamed veggies and brown rice for lunch; steamed veggies or vegetable soup and brown rice for dinner. Green or herbal teas. That’s it. I broke the news to my husband last night. “No meat, bread, dairy, sugar, no coffee,” I moaned emphatically. “Not even nuts, beans, or seeds. I’m going to have headaches and probably break out. This ruins our anniversary dinner!” Said dinner is four days out. I half-expected him to roll his eyes and agree that I shouldn’t do it. Instead, he was quiet. And within a few minutes I realized it was just homework, I could do three days instead of five, and that’s only nine meals. Instead of having to adhere to a complex, specific diet, I was given carte blanche as long as I followed the simple guidelines. No one was telling me to count calories—just eat until I was full. Where exactly was the suffering? I sighed. “OK, I get it. You’ll support me in doing my homework,” I said. He nodded. Now, the homework was assigned with two goals in mind. First, it’s a quick and gentle re-setting of our systems, a method of finding out what we are heavily dependent on and perhaps lightening that dependency. The second, as is with all spiritual “fasts,” is to remember that we are more than just our body, and more than our clamoring mind. Every grumble, every headache, is a chance to remember. I’m already two meals in. So far, I’m not suffering. This morning it was a bowl of chopped apples, which is all I had, but I went to the market and am already dreaming about tomorrow morning’s baked pears and banana. Lunch was brown rice and steamed carrots, broccoli, cabbage, string beans, and zucchini half-moons. I added chopped avocado and olive oil (allowed) to the last of the rice. It was delicious and filling. Tonight I’m baking a butternut squash, an onion, and an apple, and blending everything into soup. I can’t remember when I was so excited about vegetables. What would you make for your nine meals? Exactly one hundred years after the Panama-Pacific International Exposition reshaped my home town of San Francisco, I stood at the gates of the Expo Milano 2015. I'd always wanted to go to a World's Fair. That's where the ice cream cone made its debut (St. Louis, 1904). And the Ford Mustang (New York, 1964), baker's chocolate (1867, Paris), the telephone (Philadelphia, 1876), and color television (New York, 1939).

World's Fairs, like Burning Man, leave behind extraordinary works of public art, such as Seattle's Space Needle (1962), or San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts (1915). Which one, or ten, of the futuristic buildings constructed outside of Milan will be left standing for the next century? Too soon to tell. This fair has a serious mission. From now through October 2015, 140 countries show the best of their technology to answer to a vital need: being able to guarantee healthy, safe and sufficient food for everyone, while respecting our planet and Her equilibrium. The Expo website says it beautifully: "On the one hand, there are still the hungry (approximately 870 million people) and, on the other, there are those who die from ailments linked to poor nutrition or too much food (approximately 2.8 million deaths). In addition, about 1.3 billion tons of foods are wasted every year. For these reasons, we need to make conscious political choices, develop sustainable lifestyles, and use the best technology to create a balance between the availability and the consumption of resources." To get this message out, Milan created a park to host more than 20 million visitors in six months. My day at the Fair with my husband and daughter left me with this impression: Colossal. The Map is deceptive; it makes you think you can cover everything in a day. No way. Not only is it a long, long walk, with buildings on either side (and behind each other) packed with things to see. This wonderful drawing will give you an idea of who is participating, and here are some jaw-dropping photos of what their buildings look like. Not only are there events everywhere, and concerts in the evening. No, there's something even more colossal, even more wonderful and at the same time, rather terrifying. Every single country has provided restaurants offering its own cultural dishes. (Including, apparently, a country called McDonald's, which we did not visit). Starting at the back end (accessible by tram, no crowds), we sampled the best Indonesian chicken satay ever, followed by Turkish coffee and Pomegranate juice. Wandering, we gazed at a massive face at the Slovenia Pavilion, next to its Andy Warhol Café, admired the mirrored overhang of the Russian Pavilion, and dipped into the Sultanate of Oman to see how fishermen and bees contribute to the economy. The Expo had broken the Guinness Record for the World's Longest Pizza that day; a few thousand patrons wandered by with their wafer-thin cheese square. I was not jealous for our family had stumbled across the most amazing Brie-and-Speck pizza in a cafe that featured a Table of Elements for all pizza ingredients. I was sorry to have missed the food at the Azerbaijan Pavilion. But this could not be a walk of regrets. Rather, it whetted my appetite for more world travel. Germany showed off a brilliant public wooden bench that had lounge sections and an overhang shaded by plants. We need those here. Ecuador's building was like tropical plumage. Japanese dancers danced, Iranian women drummed, and Venezuela showed virtual sea creatures over our heads. We had considered skipping the U.S.A. Pavilion, being Americans with 139 other countries to learn from. But it was actually too cool-looking to skip. American Food 2.0 featured massive vertical farms with cabbages and leeks and corn overhead, swinging to capture the sun. Inside we watched some intriguing videos that showed America as a country of innovative immigrants, deeply concerned about regional barbecue, fruit & kale shakes, and taco trucks, a multitude of different beings brought together by the inherent generosity of our bizarre festival of Thanksgiving. You go, U.S.A. Did I mention that Michelle Obama had visited just the day before? One of our companions felt overtired, hot, and snappish, but perked up instantly in the refrigerated rooms of the Italy Pavilion's Expo de Vino. Here, more than 1,300 bottles of wine rested behind glass, separated by Italian region. Swipe your card, get an Automat pour. I was glad for the generous hunk of Parmesan they gave us, with a long, thin breadstick. As we continued, I also noticed open gyms with treadmills and bouncy balls every quarter mile or so, and good large restrooms with ice-cold water in the taps. Learn about the Expo here-- and absorb whatever strikes your fancy. We don't know which new technology or behavior is debuting at this World's Fair, but it's safe to say it will become part of our planetary food consciousness.  My book launched with its attendant fanfare and then quieted down within the expected ninety days. Since then I’ve been in an uncomfortable state of transition. I have a couple of books in messy progress, but no buyers for them and no incentive to finish them this year. I need an income and miss the comradeship of working with an office team. The job search has begun, though an upcoming trip overseas prevents me from throwing myself into the search 100%. So I’m neither here nor there, not very solvent, and feeling a little guilty. It’s the worst time to stay at home, though puppy, garden and my library do their best to keep me there. About a month ago I was really, really down. Searching job sites unleashes waves of detailed information. Piles of email notifications arrive daily. Some job descriptions remind me of skills I don't have, while searches on LinkedIn tell me that 885 other people applied for the same job as me. Like many thousands of others, I write persuasive cover letters and keyword-loaded resumes, and they sail off into silence. Enter MeetUp. One day I found my way to the site and started to pick out Meetup groups to join. Fancy meeting other human beings in a neutral place based on a common interest! The first group I attended is called Shut Up and Write. What a boon to an isolated writer. I met five people in a coffee shop. We opened our laptops and chatted while we got settled. After fifteen minutes, everyone shut up and wrote for an hour. Two people worked on their novels, another on her thesis, another on game development, and we had a blogger. It was SO helpful to hear keys tapping around the shared large table. Win, win, win. Then I started taking walks with Vintage Women. We explored new parks and neighborhoods. One day Meetup suggested a job networking group called CSix Connect. As formal and volunteer-driven as a Toastmasters meeting, CSix presents a chance to dress up and network, which pushed me into a better career groove: after the first meeting I cut my hair and ordered fresh business cards. Through the CSix meetings I found a subgroup that studies the sustainability and renewable energy industries in my area, so that I am finally connecting my interests. My current elevator speech: "I can evangelize green technologies!" The first event with Unstoppable Women of Silicon Valley netted marvelous conversations with women who are on interesting, inspiring career journeys. I came home with ten follow-up action items, feeling excited. There are four events to prepare for and attend this week, and who knows what might happen from them? It’s a little scary meeting all these new people, but I can see that it's radically increased my mental diet of positive, interesting information, and enlarged my sphere of connections across the valley.  Milkweed, thyme Milkweed, thyme I took a Sustainable Vegetable Gardening class at the community center. Taught by Master Gardeners, the class met weekly for two hours. I arrived with a dismal record for keeping vegetables and plants healthy. The land in our back yard is a tightly compacted clay that has already broken a number of my husband’s picks, rakes, and shovels. My goals: Learn about soil; feed my own compost and amend my soil; grow one thing (probably a tomato plant); and learn what plants attract bees, butterflies, and ‘beneficial insects.’ Results: I learned that I am not THAT into gardening, and decided not to build veggie beds this year. Yet I gained an almost rapturous appreciation of soil. Did you know that 2/3 of a plant’s biomass lives underground? That soil is the living edge where earth and sky meet? That the processes which occur in the top few centimeters of the earth’s surface are the basis for ALL life on dry land? 2015 has been declared an International Year of Soils. Awareness of soil is profoundly important to how we understand food security, water availability, climate change, and the alleviation of poverty. One teaspoon of composted soil (which is fluffy and smells good) contains more than 40,000 different species of yeasts, algae, and molds; seven miles of fungus filaments; 10 trillion bacteria, 100 billion fungi, 10 billion protozoa, five billion nematodes and larger critters. Fairly bursting with life. Influenced by the classes, I began feeding my lackluster compost pile with coffee grounds and all our fruit and veg trimmings, and watering it regularly. It suddenly began to act like compost! Then I put a mound of this black gold on the roots of an anemic azalea and watered it with our shower-catching bucket. Now that azalea is putting out the biggest blossoms I’ve ever seen. It wasn’t that hard. The class offered some unexpected benefits: Tips and pamphlets about drought tolerance, worm composting, handling all kinds of garden pests. A bag of mixed seeds for a wildflower garden that will attract beneficial insects! And two baby milkweed seedlings, the preferred food of the Monarch butterfly. Along the way I picked up (and planted) a baby fig tree, a healthy tomato plant, golden and silver thyme, and three fuchsia plants. So far they are all still living, the thyme even thriving. This was a useful action. |

|