|

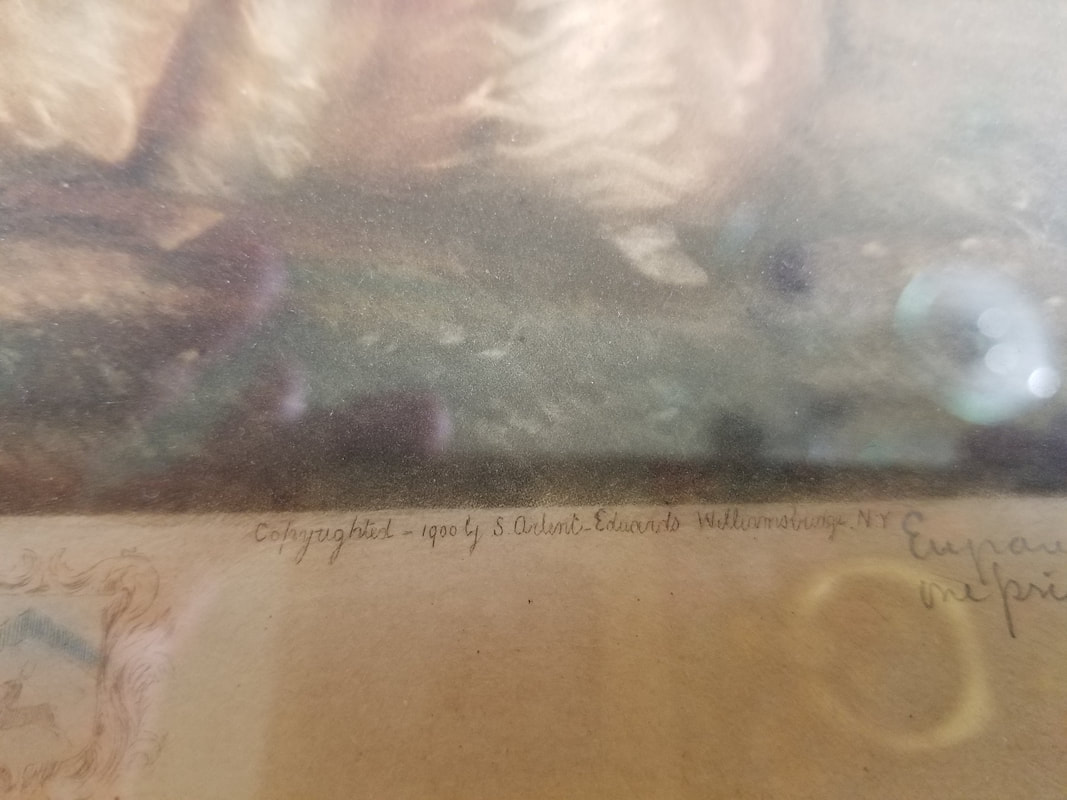

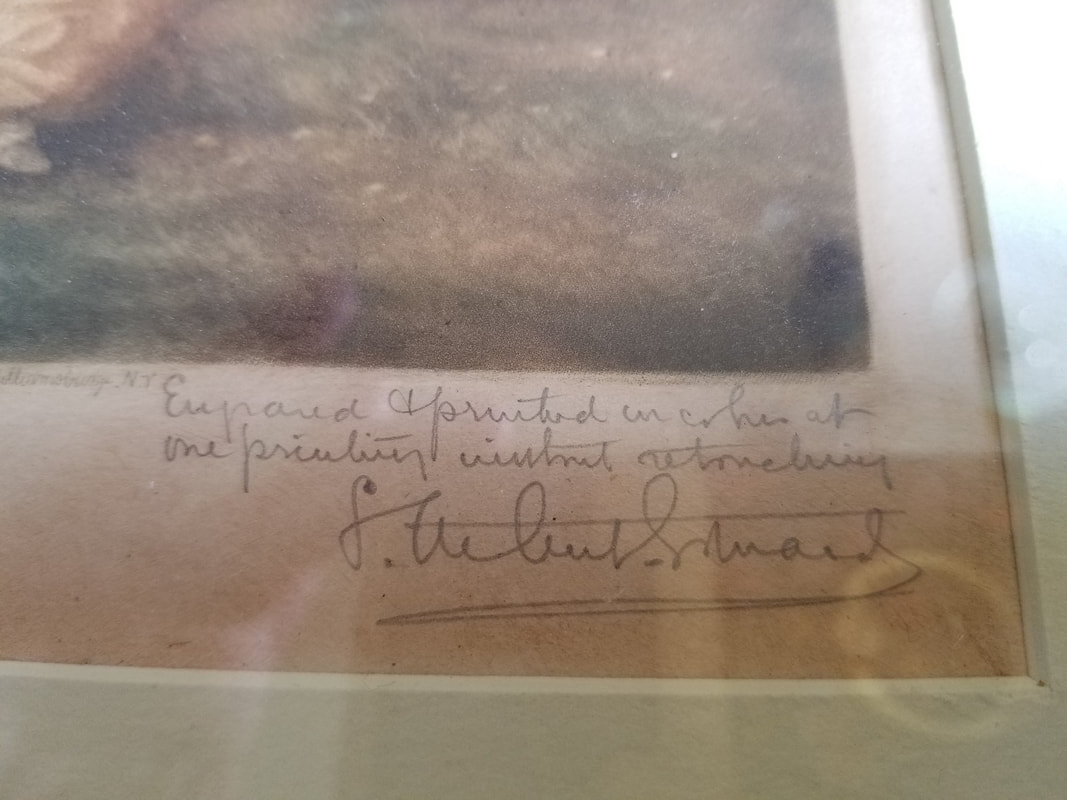

My mother was packing in preparation for a move. "Would you like to take this home with you?" she asked. "I'm not sure but it may have belonged to my mother." I liked the image, and took it home. Two years later, I was packing in preparation for a move. This print of the lady had been on my wall but frankly, it had not added a lot to my decor. It's a very quiet image, and the colors are a little muted, though warm. I called Mom and asked about it, but she couldn't remember any other details. Without a compelling family story, I wasn't sure this print would make the cut. But like anyone who's read Marie Kondo's The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up, I sat down one more time to really look at the image, and perhaps thank it before releasing it. That's when I saw this: Who was S. Arlent Edwards, where was Williamsbridge,New York, and why had he handwritten the copyright, I wondered. Then I saw this rather extraordinary statement, which, it turns out, accompanied much of his work: "Engraved and printed in color at one printing without retouching"! Turning aside from all the office work that I should have been doing, I began my research.

The plate was likely destroyed very soon after this print of the lady in the pink dress was made. Online I saw plenty of prints by Edwards, but nothing that looked like this one, so it could be rare. It appears to be a copy of "Lady Sheffield" by Gainsborough, but whereas the original is in blues, Edwards warmed up the image considerably by giving her a pink dress and bow in her hat, with a black brim as an accent. I began to like S. Arlent Edwards very much. He copied classics, which is a noble venture in itself, but then he made them his own. I learned that he was a one-man shop. Here is a wonderful description of Edwards and his mezzotint process. It's from an exhibit in the Georgetown University Library, and there are also mezzotints by Edwards in the Smithsonian. According to the curator of his exhibit, "Edwards himself inked and printed each plate for every copy, and therefore no two prints were exactly alike. He made only a limited number of copies of each work, insisting that each be sold framed, and then he destroyed each plate." "The process is unforgiving of error or impatience, but allows unsurpassed delicacy of line, color shading, and texture. It was perfectly suited to Edwards' interest in such fine aspects of old masters' work, and his attention to the details of their paintings resulted in creative reinterpretations that are far more than mere reproductions. Not only are they acts of homage, they are also original works of art in their own right." I wrote to my mother, telling her all this, in case she wanted to keep it. But now I felt affection for this print, affection for the printer, and curiosity about Lady Sheffield. What was her story? Would it be something I could research and write about? And which of our relatives chose her from a New York gallery and framing shop around the year 1900? And why did they choose this one instead of Edwards' more popular "George Washingtons" and Bellini copies? Could they have also been intrigued by the substitution of the pink dress? Mom replied, "this is great research - more power to you! (About the family members) Frankly, I don't remember - somehow I think Amistad [her father's parents' home], but it may have been Grammy, too [her mother's mother] - it doesn't much matter at this point. I just like to think of her being well cared for. . . " And maybe after all, the family story that was once attached doesn't much matter at this point. I appear to have formed my own, and the print will stay with me and my family. With some of the research in an envelope, taped to the back. Exactly one hundred years after the Panama-Pacific International Exposition reshaped my home town of San Francisco, I stood at the gates of the Expo Milano 2015. I'd always wanted to go to a World's Fair. That's where the ice cream cone made its debut (St. Louis, 1904). And the Ford Mustang (New York, 1964), baker's chocolate (1867, Paris), the telephone (Philadelphia, 1876), and color television (New York, 1939).

World's Fairs, like Burning Man, leave behind extraordinary works of public art, such as Seattle's Space Needle (1962), or San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts (1915). Which one, or ten, of the futuristic buildings constructed outside of Milan will be left standing for the next century? Too soon to tell. This fair has a serious mission. From now through October 2015, 140 countries show the best of their technology to answer to a vital need: being able to guarantee healthy, safe and sufficient food for everyone, while respecting our planet and Her equilibrium. The Expo website says it beautifully: "On the one hand, there are still the hungry (approximately 870 million people) and, on the other, there are those who die from ailments linked to poor nutrition or too much food (approximately 2.8 million deaths). In addition, about 1.3 billion tons of foods are wasted every year. For these reasons, we need to make conscious political choices, develop sustainable lifestyles, and use the best technology to create a balance between the availability and the consumption of resources." To get this message out, Milan created a park to host more than 20 million visitors in six months. My day at the Fair with my husband and daughter left me with this impression: Colossal. The Map is deceptive; it makes you think you can cover everything in a day. No way. Not only is it a long, long walk, with buildings on either side (and behind each other) packed with things to see. This wonderful drawing will give you an idea of who is participating, and here are some jaw-dropping photos of what their buildings look like. Not only are there events everywhere, and concerts in the evening. No, there's something even more colossal, even more wonderful and at the same time, rather terrifying. Every single country has provided restaurants offering its own cultural dishes. (Including, apparently, a country called McDonald's, which we did not visit). Starting at the back end (accessible by tram, no crowds), we sampled the best Indonesian chicken satay ever, followed by Turkish coffee and Pomegranate juice. Wandering, we gazed at a massive face at the Slovenia Pavilion, next to its Andy Warhol Café, admired the mirrored overhang of the Russian Pavilion, and dipped into the Sultanate of Oman to see how fishermen and bees contribute to the economy. The Expo had broken the Guinness Record for the World's Longest Pizza that day; a few thousand patrons wandered by with their wafer-thin cheese square. I was not jealous for our family had stumbled across the most amazing Brie-and-Speck pizza in a cafe that featured a Table of Elements for all pizza ingredients. I was sorry to have missed the food at the Azerbaijan Pavilion. But this could not be a walk of regrets. Rather, it whetted my appetite for more world travel. Germany showed off a brilliant public wooden bench that had lounge sections and an overhang shaded by plants. We need those here. Ecuador's building was like tropical plumage. Japanese dancers danced, Iranian women drummed, and Venezuela showed virtual sea creatures over our heads. We had considered skipping the U.S.A. Pavilion, being Americans with 139 other countries to learn from. But it was actually too cool-looking to skip. American Food 2.0 featured massive vertical farms with cabbages and leeks and corn overhead, swinging to capture the sun. Inside we watched some intriguing videos that showed America as a country of innovative immigrants, deeply concerned about regional barbecue, fruit & kale shakes, and taco trucks, a multitude of different beings brought together by the inherent generosity of our bizarre festival of Thanksgiving. You go, U.S.A. Did I mention that Michelle Obama had visited just the day before? One of our companions felt overtired, hot, and snappish, but perked up instantly in the refrigerated rooms of the Italy Pavilion's Expo de Vino. Here, more than 1,300 bottles of wine rested behind glass, separated by Italian region. Swipe your card, get an Automat pour. I was glad for the generous hunk of Parmesan they gave us, with a long, thin breadstick. As we continued, I also noticed open gyms with treadmills and bouncy balls every quarter mile or so, and good large restrooms with ice-cold water in the taps. Learn about the Expo here-- and absorb whatever strikes your fancy. We don't know which new technology or behavior is debuting at this World's Fair, but it's safe to say it will become part of our planetary food consciousness.  Milkweed, thyme Milkweed, thyme I took a Sustainable Vegetable Gardening class at the community center. Taught by Master Gardeners, the class met weekly for two hours. I arrived with a dismal record for keeping vegetables and plants healthy. The land in our back yard is a tightly compacted clay that has already broken a number of my husband’s picks, rakes, and shovels. My goals: Learn about soil; feed my own compost and amend my soil; grow one thing (probably a tomato plant); and learn what plants attract bees, butterflies, and ‘beneficial insects.’ Results: I learned that I am not THAT into gardening, and decided not to build veggie beds this year. Yet I gained an almost rapturous appreciation of soil. Did you know that 2/3 of a plant’s biomass lives underground? That soil is the living edge where earth and sky meet? That the processes which occur in the top few centimeters of the earth’s surface are the basis for ALL life on dry land? 2015 has been declared an International Year of Soils. Awareness of soil is profoundly important to how we understand food security, water availability, climate change, and the alleviation of poverty. One teaspoon of composted soil (which is fluffy and smells good) contains more than 40,000 different species of yeasts, algae, and molds; seven miles of fungus filaments; 10 trillion bacteria, 100 billion fungi, 10 billion protozoa, five billion nematodes and larger critters. Fairly bursting with life. Influenced by the classes, I began feeding my lackluster compost pile with coffee grounds and all our fruit and veg trimmings, and watering it regularly. It suddenly began to act like compost! Then I put a mound of this black gold on the roots of an anemic azalea and watered it with our shower-catching bucket. Now that azalea is putting out the biggest blossoms I’ve ever seen. It wasn’t that hard. The class offered some unexpected benefits: Tips and pamphlets about drought tolerance, worm composting, handling all kinds of garden pests. A bag of mixed seeds for a wildflower garden that will attract beneficial insects! And two baby milkweed seedlings, the preferred food of the Monarch butterfly. Along the way I picked up (and planted) a baby fig tree, a healthy tomato plant, golden and silver thyme, and three fuchsia plants. So far they are all still living, the thyme even thriving. This was a useful action. Yes it’s a dry spring in California. Nonetheless plant and vegetable and tree roots inch along, lengthening as they reach for water and warmth. That word ‘lengthen’ shares a root with the Festival of ‘Lent,’ also occurring now.

The Catholic season of Lent is about removing distractions, sending our own attention and energy inward and downward, a forty-or-so day meditation before we flower into action. Indeed, a radical action is one expressed from our root. I attended a gathering of about four hundred souls last weekend, a mix of farmers and urbanites, natives and immigrants, scientists, writers, artists, meditators, gardeners, and activists — we filled up a whole school in the town of Point Reyes Station. At the conference, called Mapping a New Geography of Hope, we listened to really thoughtful people getting at the root of things. The planet is heating up. People are acting badly. Others do healing and reparation of wrongs done to our forests, cultures, and oceans, and still others create necessary visions and plans for a good life on a healthy planet with sustainable, balanced systems. Which gave me the questions to ponder: · What do I love too much to lose? · What will I do to protect what I love? · What does the Earth ask of us? With my own talents, what are my responsibilities? · What can be gathered from our ancestors, and from local ancestors (for me Silicon Valley and the Bay Area), that will help us heal our land and water? · How am I letting my attention and body be colonized by corporate interests? · Why are rhinos, bears, monkeys and sharks being slaughtered to extinction for increased sexual potency? · How can I, in a nation that uses 30 times the resources of other nations, calm my own consumer desires? · How can I shape the next chapter of the Silicon Valley / Bay Area story? One of my heroes will arrive soon in my metropolis. Actually, she is also bringing several of my heroes with her.

This is not a paid announcement; Oprah and her extensive staff have no idea of my existence. But the fact of her coming to what we still call “The Shark Tank” in downtown San Jose—and that I am going to spend an evening and a day as part of the audience--seems so mighty as to be blog-worthy. I came to Oprah late. You can find all kinds of stories about her success in television: the boundaries her show pushed, her rise through multiple glass ceilings. Not much of a TV watcher at the time, I first found her while sifting through the library’s free magazine box for collage materials. I judged O Magazine to be an excellent source of colorful images and paper (it still is. So is Martha Stewart Living). Over time, my issues of O magazine grew too full of relevant articles and pithy wisdom to cut up. I bought a subscription. Oprah had already started building an academy for girls in the Gautang province of South Africa; she produced movies; the episode where she dragged a wagon of lost fat onstage was already legend. She graduated from her TV show and began to tackle the huge issues of running a network. That's when my love affair with her "Super Soul Sunday" program began. I record the shows and dip into them while I make dinner on weekdays. With the advent of her interviews with people whom I can only describe as "awake," I realized Oprah herself has become one of my strongest spiritual teachers. She delights in wisdom, refuses to stick to one dogma, and broadcasts what she finds. She's creating and maintaining a world-class interfaith seminary, freely open to anyone with access to a television. I hold her in a category with Joseph Campbell, Carl Sagan, and Dr. Matthew Fox. She walks her talk and puts her money behind these lofty goals. I want to do something good in the world like she does. My other heroes who might be there: Elizabeth Gilbert, Dr. Deepak Chopra, Iyanla Vanzant, and Rob Bell. The show is titled “The Life You Want,” and I feel blessed to be already leading one, so I don’t plan to change course radically. But I am drawn to these beautiful souls, and want to absorb as much wisdom I can. It easy for me to tell that autumn has come. I find myself reaching for long-sleeved shirts and boots, thinking about food.

A restless urge stirs inside me so that I sort through my bookshelves, releasing seven bags of books I no longer need. And I think about food. I’m compelled to sort the family’s flannel sheets and throw out plastic lids with no containers, thinking wildly about food. Fall food. Roasted butternut-apple-onion soup. Roasted beets in mango balsamic vinaigrette. Kubocha pumpkin soup --- it doesn’t get any easier. Roast it and purée with the stock of your choice. If you want to get fancier, quinoa salad with minced red onion, feta, orange segments, arugula, cilantro, mint, and chopped dried cranberries and apricots. Slivered almonds optional. Oatmeal with persimmon, banana, walnut, and cranberry. No sugar or milk needed. Pears baked in apple juice with cinnamon and vanilla. Or just an Asian pear (also called apple pears) thinly sliced, with a cup of ginger honey tea. Mmmmmmmmmm.  Floods of information and inspiration poured forth from the AWP conference in Seattle. Thousands and thousands of writers congregated with editors, publishers, poets, teachers, and students. I recognized my tribe. In packed rooms I scribbled notes as speakers addressed subtleties in spiritual writing, researching historical novels, nature essays, regional poetry. One night I heard Eva Saulitis, a marine biologist, teacher, writer, and poet (and beekeeper), describe long, cold months observing orca whales. She described how the boredom, the waiting, the emptiness were aspects of imagination, precursors of her work. The work, she said, came from the intersection of “data collection and awe.” I arrived home with so much to think about. My craft and direction were reconfirmed. I found leads to publish work. I made friends, growing a community that suddenly spans the globe. I heard new models of writing and carted home pages of notes toward the New Book, skills in Twitter, goals for blogging, and a writing schedule to try out. And enough literary magazines to pull my shoulder out of whack. It was an overabundance. I swam in it for three weeks after the conference. * * * Neighborhood crows flap heavier these days because their beaks are filled with sticks. They are building nests, of course, as I build scaffolding for my new book. “Pairs function as highly synchronized teams, building large, stick-based nests, carefully lining them with fine rootlets or hair.” (Marzluff and Angell, In the Company of Crows and Ravens.) An initial web of ladders and planks give workers safe access to transform all parts of a structure. For a book, scaffolding might include an outline, a timeline, a narrative arc plotted on a whiteboard or paper. I also build a schedule on paper and in Google. The schedule must include walks, library research, fieldwork, and snacks of music, books, drawing, museum visits. “Crows take a great deal of time choosing the sticks they want to use in the construction of their nests.” (Haupt, Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom From the Urban Wilderness.) The scaffold also serves to protects the act of writing itself, because life is so full with family, other work, events, friends. I keep re-learning that limits must be set. “The crow’s nest is a remarkably intricate piece of work, belying both the rough exterior of the structure and the bulkiness of its creators.” (Haupt) At this time, it's better for me to dwell inside the book for several days or weeks at a time, listening to echoes and characters, without forced interruptions to broadcast content. See you in a few weeks. This week I'll join more than 12,000 other writers and editors, professors, agents and students at an extravaganza called AWP. It's my first one.

I'll bring a small rolling bag and a black daypack to carry snacks, my itinerary, aspirin, some old sweaters, and empty journals. But that's my toolkit, not baggage. The things I will NOT be lugging around (and I was certain that I would):

There is, in fact, very little on the horizon. As though the Universe is sweeping everything from my path, with Infinite Love, and telling me to get to work on the art right under my nose. I feel so untethered. Tomorrow I head north, and plan to go in a state of quiescent listening!  On my way to a Saturday morning study group, I idle at the red light on Winchester. My car faces south toward Los Gatos. My mind is as neutral as my engine. To my right two small silver cars arrive side by side, almost pushing each other out of the way to make their respective turns. The farther car begins to rise, like a gleaming helium balloon, and continues to rise until it is over the nearer car. High in the air it arcs and rolls in a slow, elegant spiral, almost pausing, then plummets on its head on the asphalt in the middle of Winchester. Now I understand the phrase, “scarcely believe my eyes.” The car does not move. I must assume this has happened, not in a waking dream, but in the world. I pull my car over, park, and stumble out to help. It is immediately apparent that I will not be able to open the crushed door, and other people begin to form around the car, so I turn back with shaking hands to find my cell phone. 911 brings forth a busy signal. I try it again, again, again, and five times, the busy signal. At nine on a Saturday morning. But others also hold their cell phones, more beginning to arrive from a nearby café, and one woman appears to be talking, so she has gotten through. Nothing moves inside the car. The morning sky remains blue. The street remains quiet. The driver of that car was in a hurry. What was he, if it was a he, heading toward? Was he coming home from a late night? Was he eager to get to the gym? How did he not see the orange plastic barriers, temporary barriers, to his right, surrounded by neon cones? His mind was preoccupied. He assumed that everything around him would run smoothly so he could think his thoughts unmolested, as we always assume. So much of our lives must run smoothly. Hot water cascades from the shower head. Drivers stay in their lanes. An e-mail is sent and arrives at its destination. For the most part. He assumed that it would not affect the course of his day if he gave into a momentary feeling of impatience by stepping on the accelerator. We do it all the time. People gather around the driver’s side as a police siren grows louder and its lights appear down the street. No one else is on the passenger side to see what I see next. The flattened, upside-down door opens and two legs emerge, tangled in a black seat belt strap. The feet, in white running shoes, touch the ground. Then all is still again. My feet move toward the car. It is a man. This morning he put on faded blue jeans and white shoes. He had been impatient to get somewhere. He meant to go left, or perhaps right. The front tire of his car found contact with the lowest part of an orange plastic barrier, the thinnest edge of the wedge, and obeying the laws of physics, the tire followed its natural path up the vertical slope of the barrier. The tire, the vector, had no choice. The car was perhaps surprised to find itself aloft, so high and quiet against the blue sky of a Saturday morning, perhaps nothing in its manufacture had prepared these tons of metal and glass to float, to float for a full second before the earth pulled it to herself with decisive arms. After a moment, I saw the man emerge, his eyes wide, hand to his white cheek while speaking to the police officer. Had he died I might not be able to describe to you that terrible beauty, that silver car following its path into the air, that arc, that nautilus, that whorl of your soft hair, that silent curve against the morning blue that haunts me even now.  What makes you feel wealthy? I don’t mean measuring the size of your bank account, but the wealth of having enough, the feeling that as long as I have this, I’m OK. One recent emblem of abundance for me has been having a bowl of coral-gold persimmons on my table. Especially when they come from a neighbor’s tree -- they can be expensive in the market! When I see the bowl, I know that I can have a sweet, luscious snack every day if I feel like it, and it will be good for me. The color just makes me smile. I did not know how to eat fuyu persimmons until my friend, Jocelyn, modeled the proper fuyu eating stance. We were having a discussion and I watched as she took a persimmon and a small, sharp knife. She simply carved slices off the persimmon and handed one to me. I was shocked at how good it tasted. The other kind, the Hachiya pictured here, might need a long time to ripen into jelly, and can be eaten with a spoon. Here is the other thing that makes me feel ready to take on the world: I realize how old-fashioned I will sound, but I feel wealthy when I can carry postage stamps in my wallet. Especially those with brilliant pictures on them of dancers or musicians, or wise men and women of history, or flowers. I know I can mail anything on the spur of the moment—an urgent bill perhaps, but more importantly, a fan letter or a thank-you note. I hated it as a child when my Mom made me sit and write thank-you notes after Christmas and birthdays, but now I'm glad she did; years of experience have taught me how simple it is to jot a note, find the address, add a stamp, and pop it into the mailbox. You never know what a huge impact a little letter in the mail can make. As I came to realize how many authors work in a vacuum of silence, just like me, and how their books get published to a little fanfare and then get swallowed up by even greater silence, I realized that fan letters are as important as thank you notes. It was a little intimidating, writing to the first author I admired, but I am so glad I did. She sent me a brief reply on a postcard that showed a watercolor painting of a French bakery. Nourishing indeed! I think stamps mean so much to me because of times in the past when I was traveling and did not have the money to eat more than once every couple of days. I really wanted to send a letter to my family, but did not have the postage, let alone enough to place an international call. So yes, my wallet contains two sleeves of stamps. And I have clean, warm socks on my feet. I feel like a million dollars, and I think I’ll go eat a persimmon. |

|