|

I've been getting gentle nudges from my great-grandmother, Helen van Loben Sels -- and so is my cousin Karen Minton, all the way in Whitefish Montana!

Here in San Jose, I was discussing creative blocks with my friend Marc who is a superb creative development advisor. You can read more about Marc and his wisdom on this page. During that conversation I realized that I wanted to give Helen and the Masters a bigger and better push into the world, so that little book will find its way into the right hands. When I published the book in July 2020, I had Covid-tide mental exhaustion, was working full-time, had downsized our family home and was waiting to move into the smaller one. I could scarcely gather the energy to put up a web page about the book. But time plodded on, my circumstances slowly shifted and I recovered my focus and passion. As Marc and I were talking, Karen, a remarkable painter, gave herself an assignment of 100 watercolor portraits in 100 days. Somehow, our 'Amama' keeps popping up for her. One of the things we are now discussing among cousins is the color of Amama's eyes. I'm pretty sure they will be confirmed as blue, but the brown-eyed portrait that Karen painted seems to be filled with Helen's spark of life. She's looking at me and encouraging me. Isn't it interesting when one ancestor inspires descendants who live so far apart? Julia Palmer met Morris W. Smith in New York City in the fall of 1845. At twenty-nine, she was ten years his elder, and they became friends, comrades. Several men closer to Julia's age took her to the opera, to art exhibits, to dine, but she also enjoyed quiet evenings conversing with Morris in the parlor of their shared boarding house. (There were about 60 boarders there, mostly young men studying or starting in the professions.)

After Julia returned home in February 1846, they continued their friendship through letters, jokingly addressing each other as "brother" and "sister." Morris's family business kept him in New Orleans through the fall, winter and spring months. In April 1848 Morris visited Julia at her parents' home in Brockport, New York, and they became engaged. That's after TWO YEARS of writing letters, first as just friends. Over time, I think they both began to realize that they could speak frankly about their hopes and dreams to each other, something they had not found in the people actually surrounding them. Morris and Julia were both smart, and they shared a passion for books. They each loved their parents, and they worked hard at whatever was in front of them. They admitted to faults, and tried to be good people, and to help each other become better. And they teased each other about small things, but kindly. Over time the tone of their letters changed. They became more tender. And one February day in 1847, Morris signed his letter: "Your brother, servant, slave, or anything so long as I can call myself yours." Julia did not answer that letter directly. Eight months later, Morris slipped another taste of romance into his letter, calling her "mavourneen," Gaelic for "my beloved." Four months after that, she actually addressed him for the first time as "Dear" Morris. Subtle, right? The next month, they met again and were engaged. More to come soon. This post, and the next few, are about love. But not modern love.

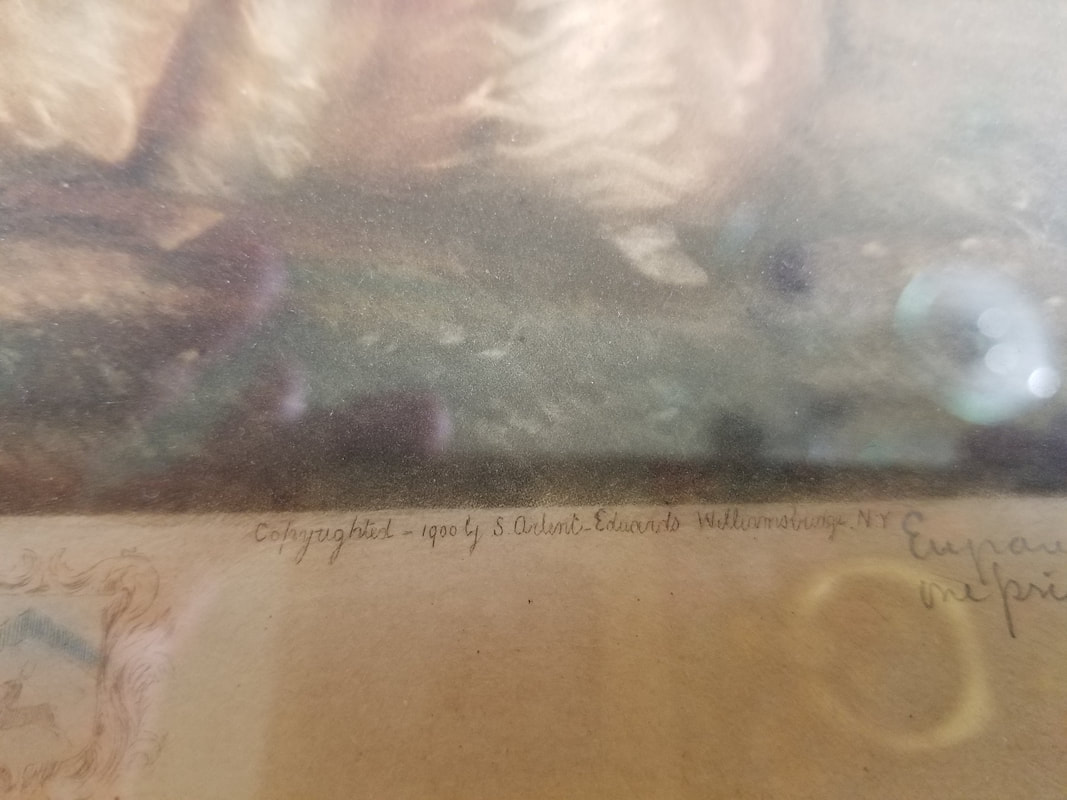

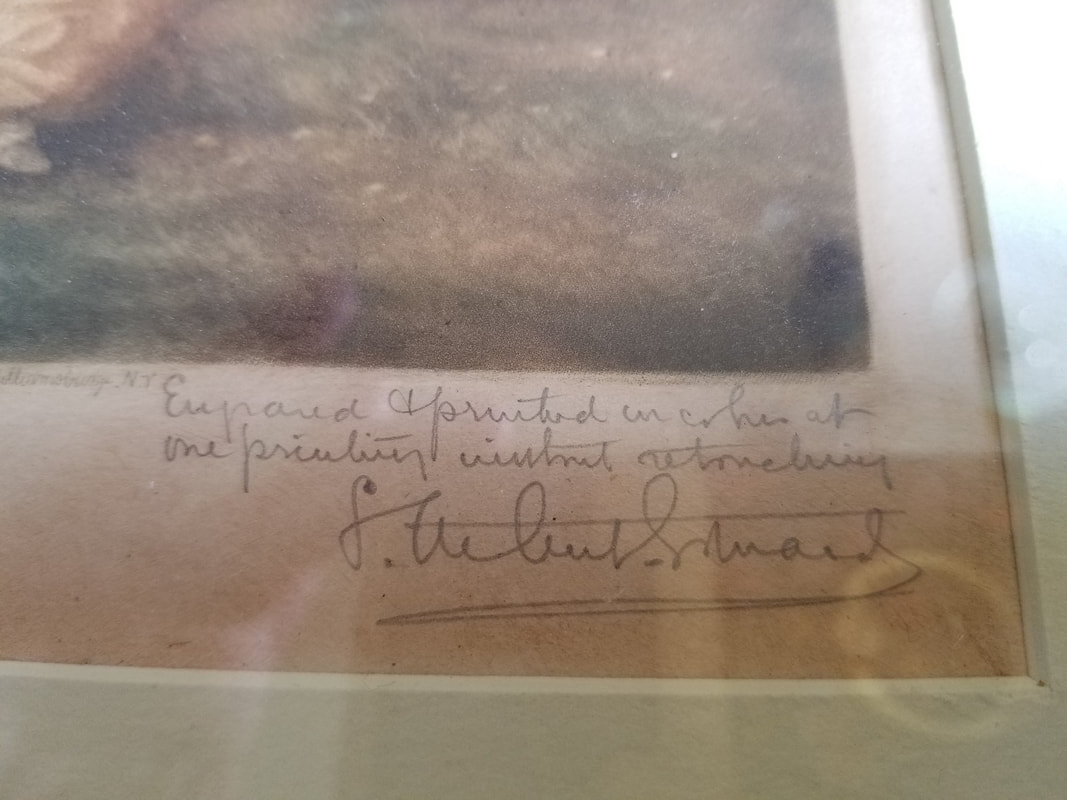

I recently borrowed, from one of our family archivists, about a thousand letters between my great-great-great Grandmother Julia Palmer and my great-great-great Grandfather Morris Smith. I am reading a few letters every day, seeking a story I might write about their extraordinary lives. In order to write letters, you need absence, love, and a strong desire to communicate -- and for nearly forty years, Morris had to stay in New Orleans to work for his brothers from six to nine months out of each year, while Julia and their four daughters stayed up North in Hartford, Connecticut. Reading these letters of love and longing, of domestic details and gentle teasing, I begin to see scenes and cloudy outlines of America in the 1840s through the 1880s. I'm less than a third of the way through, but already I am fascinated, and I thought I'd share some pieces with you, who might be thinking of getting married or officiating at someone's wedding. I'll post some words soon that Julia and Morris told each other as they fell in love, and in future posts, some of their more mature love as it shines through the letters. Julia went on to become a successful novelist, even earning enough to build a wonderful home! But between you and me, it was a few of Morris's letters that actually brought tears to my eyes. Stay tuned. My mother was packing in preparation for a move. "Would you like to take this home with you?" she asked. "I'm not sure but it may have belonged to my mother." I liked the image, and took it home. Two years later, I was packing in preparation for a move. This print of the lady had been on my wall but frankly, it had not added a lot to my decor. It's a very quiet image, and the colors are a little muted, though warm. I called Mom and asked about it, but she couldn't remember any other details. Without a compelling family story, I wasn't sure this print would make the cut. But like anyone who's read Marie Kondo's The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up, I sat down one more time to really look at the image, and perhaps thank it before releasing it. That's when I saw this: Who was S. Arlent Edwards, where was Williamsbridge,New York, and why had he handwritten the copyright, I wondered. Then I saw this rather extraordinary statement, which, it turns out, accompanied much of his work: "Engraved and printed in color at one printing without retouching"! Turning aside from all the office work that I should have been doing, I began my research.

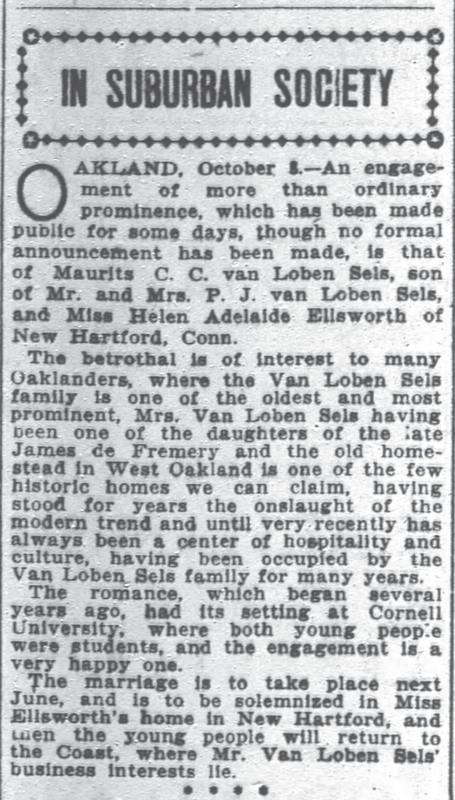

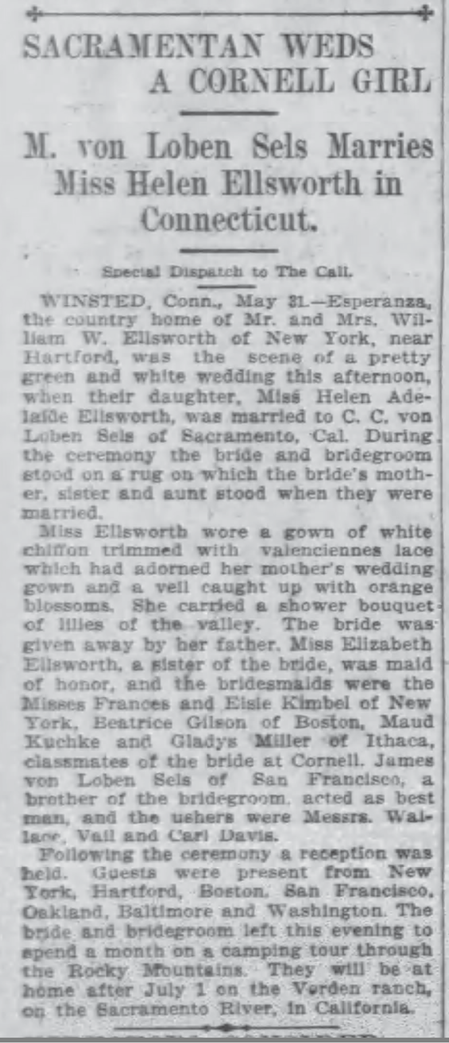

The plate was likely destroyed very soon after this print of the lady in the pink dress was made. Online I saw plenty of prints by Edwards, but nothing that looked like this one, so it could be rare. It appears to be a copy of "Lady Sheffield" by Gainsborough, but whereas the original is in blues, Edwards warmed up the image considerably by giving her a pink dress and bow in her hat, with a black brim as an accent. I began to like S. Arlent Edwards very much. He copied classics, which is a noble venture in itself, but then he made them his own. I learned that he was a one-man shop. Here is a wonderful description of Edwards and his mezzotint process. It's from an exhibit in the Georgetown University Library, and there are also mezzotints by Edwards in the Smithsonian. According to the curator of his exhibit, "Edwards himself inked and printed each plate for every copy, and therefore no two prints were exactly alike. He made only a limited number of copies of each work, insisting that each be sold framed, and then he destroyed each plate." "The process is unforgiving of error or impatience, but allows unsurpassed delicacy of line, color shading, and texture. It was perfectly suited to Edwards' interest in such fine aspects of old masters' work, and his attention to the details of their paintings resulted in creative reinterpretations that are far more than mere reproductions. Not only are they acts of homage, they are also original works of art in their own right." I wrote to my mother, telling her all this, in case she wanted to keep it. But now I felt affection for this print, affection for the printer, and curiosity about Lady Sheffield. What was her story? Would it be something I could research and write about? And which of our relatives chose her from a New York gallery and framing shop around the year 1900? And why did they choose this one instead of Edwards' more popular "George Washingtons" and Bellini copies? Could they have also been intrigued by the substitution of the pink dress? Mom replied, "this is great research - more power to you! (About the family members) Frankly, I don't remember - somehow I think Amistad [her father's parents' home], but it may have been Grammy, too [her mother's mother] - it doesn't much matter at this point. I just like to think of her being well cared for. . . " And maybe after all, the family story that was once attached doesn't much matter at this point. I appear to have formed my own, and the print will stay with me and my family. With some of the research in an envelope, taped to the back. I've been writing my Masters' thesis, a slim biography about my maternal great-grandmother, for three years. At first the book was mostly in my head as I struggled with structure and voice. Finally, scenes began to find their way onto paper. During year two, I constructed a long, awkward 'spine' of a book with clunky pieces. I was still in the gathering and placing phase, and many of the pieces went off in all directions. It was such a mess! I shared it with friends who gently reflected back that yes, it was such a mess. Still, the book had come alive now, and we were in a rather obsessive relationship. This summer, in shifts of between one and four hours of work on it every day (and dreaming about it all the time), I managed to cut and sand away the rough edges, find an internal logic, and let the story begin to shine by itself. I didn't answer all the questions I had about her, but now I could see parts of her life more clearly. I'm a month away from submitting it to the first committee for their round of edits, and I have not performed a wedding for a year. And yet. Weddings are around me, I remember them, I think about them. Here is a clipping about my great-grandmother's engagement to my great-grandfather. . . And here is what the wedding was like: Somewhere I have a blurry grey and white photo of the couple, but I actually think the reporter's breathless words do them better justice. A gown trimmed with Valenciennes lace! Orange blossoms on her veil! My family remembers that the wedding took place in the 'keeping room' because it was a little too chilly to hold outside. The keeping room is where dairy products were kept at a steady temperature. My guess is that the milk and butter were removed, and the room was filled with flowers.

Thank you for reading, and wish me luck on this thesis. |

|